Do Attacking Players play more Forcing Moves?

Finding forcing moves and looking through the games of world championsWhen I think about attacking chess, forcing moves are the first thing that come to mind. But I never really thought about whether attacking players actually play more forcing moves compared to more positional players.

So I want to investigate this by looking through the games of a couple of world champions and see if the number of forcing moves can be an indication of the style of a player.

Defining forcing moves

The standard definition of a forcing move is a check, a capture or a threat.

Checking whether a move is a check or capture is straightforward. I excluded recaptures from the forcing moves, as a recapture is a reaction to a forcing move rather than a forcing move in itself.

However, detecting threats is more complicated.

I’ve written a post in the past about detecting threats using Stockfish. But this approach isn’t suitable for the current situation, as I want to go through thousands of games and therefore tens of thousands of moves. So even spending half a second for Stockfish to analyse each move isn’t feasible.

So I needed to define which kind of moves are counted as threats more concretely.

I limited myself to counting moves that attack an undefended pawn or piece, moves that attack a higher valued piece and mate in 1 threats.

There are many other things I could have included, like moves that set up a tactic, or longer mate threats. The problem is that checking these things takes again computing time, as one would need to calculate a couple of moves ahead for each move played.

Looking at different players

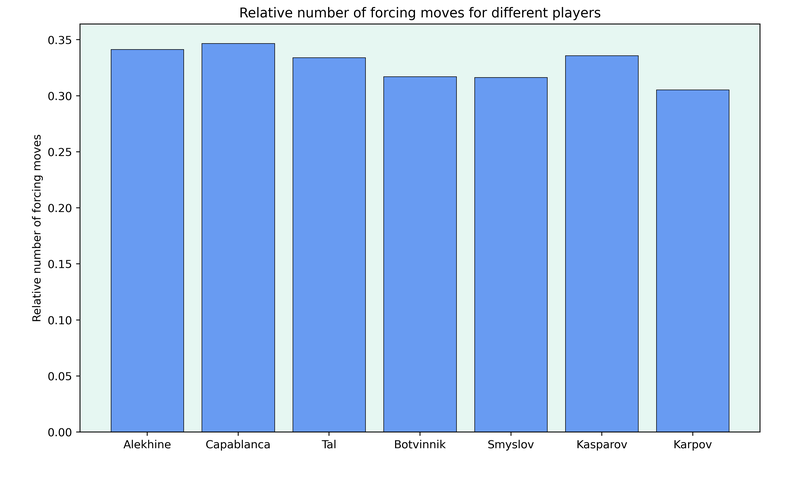

Now that we have a way to identify forcing moves, we can look at the relative number of forcing moves different players play.

I decided to look at a couple of historical world champions which had a relatively clear style and see how the number of forcing moves they played compares to each other.

The differences between the players are slight, but Kasparov and Tal played more forcing moves than their more positionally inclined competitors. However, the story is different for Alekhine and Capablanca, where the more positional player actually played more forcing moves.

So it seems like the forcing moves aren’t a completely reliable tool to identify attacking players, which was to be expected. But I think that the relation is relatively strong, especially since looking at players before the 1950s is always more difficult, as they played many tournament games against much weaker opposition and had fewer games overall, which makes the data more noisy.

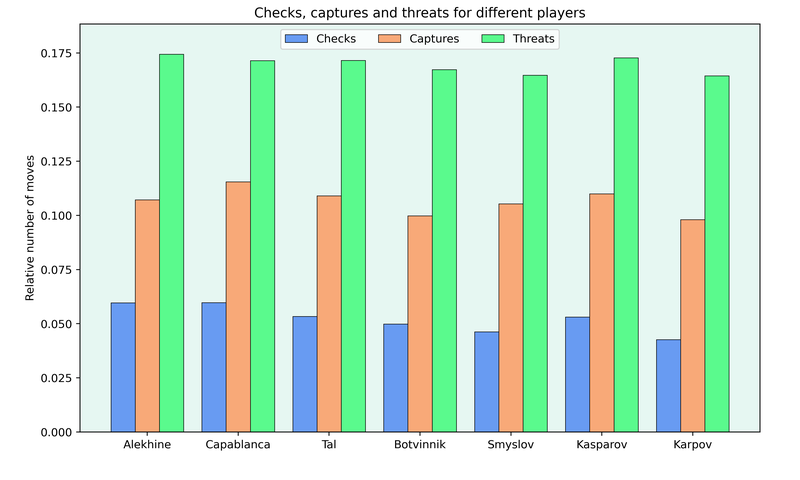

I was also interested to see whether there is a difference between the different types of forcing moves.

It’s interesting to see that most of the forcing moves are threats, especially since there are more types of threats which I didn’t count. But there is not one type of forcing move that is more commonly played by attacking players compared to more positional players. The relative number of checks, captures and threats reduces evenly for the more positional players.

If you enjoy this post, check out my Substack.

Conclusion

It’s nice to see that the number of forcing moves correlates at least roughly with my feeling of the styles of the players.

A single value like this is obviously not enough to determine the style of a player, but I want to use it for a future iteration of my player classification project. There are some other variables that I want to include and my hope is that the classification gets more accurate once I use more data.

Let me know what you think about my findings and if there are some other types of moves that might be worthy of a closer examination.

You may also like

jk_182

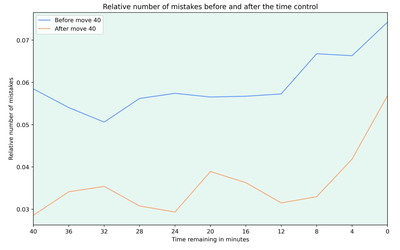

jk_182How does the Clock impact the Rate of Mistakes?

Looking at the relative number of mistakes depending on the time left on the clock thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… jk_182

jk_182How the World Cup Format impacts Results

Taking a look at all matches from previous world cups jk_182

jk_182How Opening Advantages Translate into Results in Online Games

Measuring conversion rates in online blitz and bullet games for 1200 to 2400 rated players CM HGabor

CM HGabor